Description

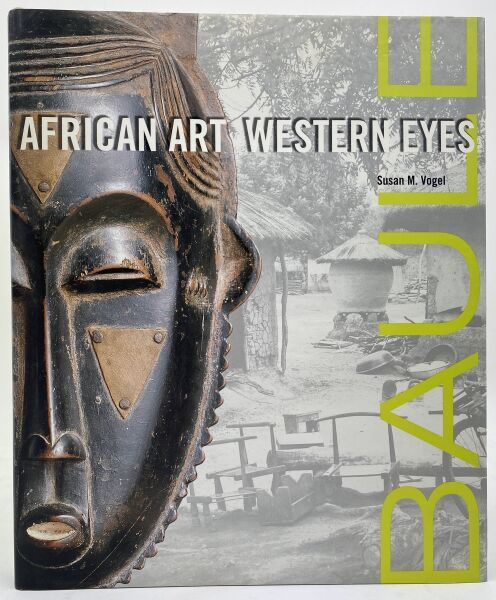

VOGEL MULLIN SUSAN. Baule: African Art Western Eyes. Ed.David Frankel-Yale University Press 1997, in-4 beige cloth binding and illustrated dust jacket.

30

VOGEL MULLIN SUSAN. Baule: African Art Western Eyes. Ed.David Frankel-Yale University Press 1997, in-4 beige cloth binding and illustrated dust jacket.

You may also like