Description

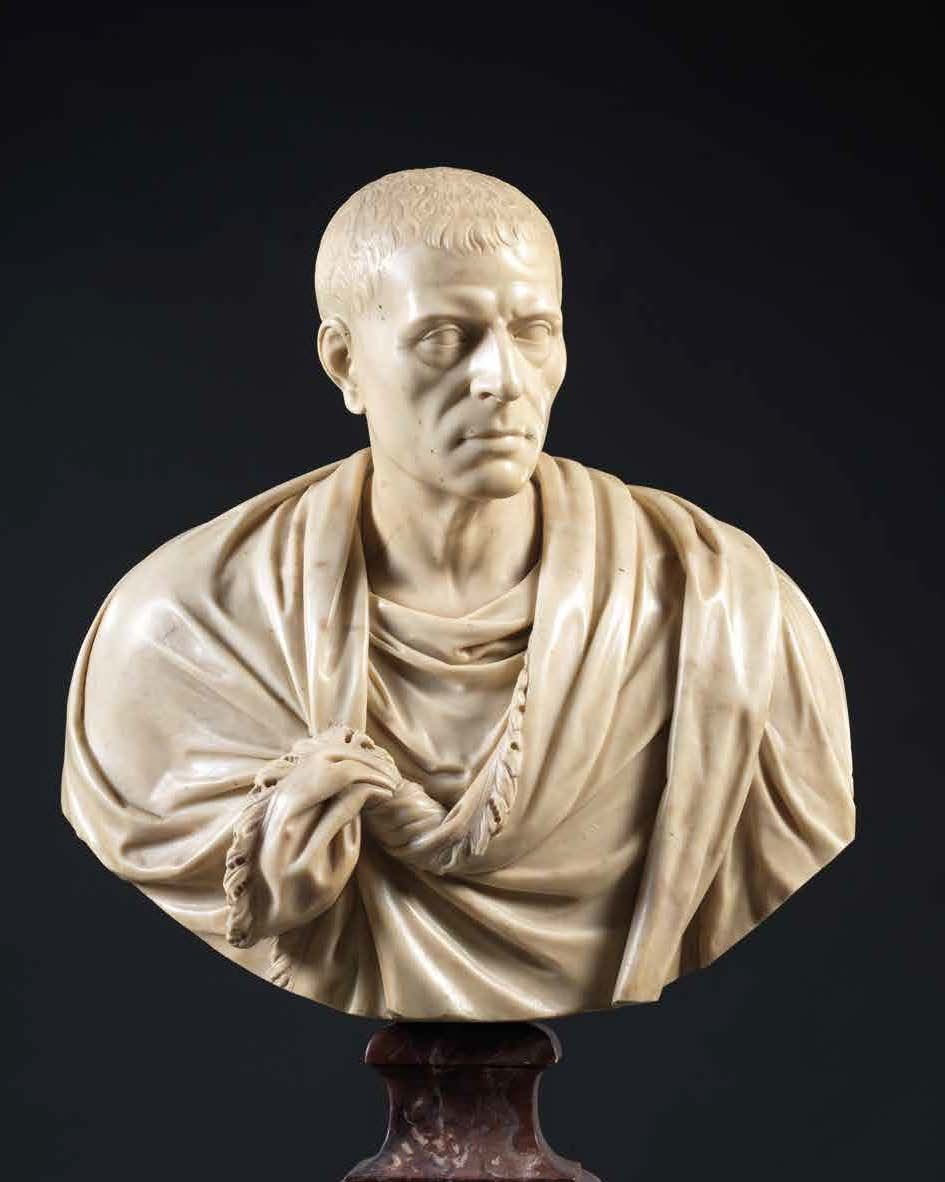

TWO BUSTES forming a counterpart OF ROMAN STATE MEN BUSTE OF CICERON Italy, late 17th century White marble; painted wooden pedestal in imitation of marble H. 81 cm, W. 60 cm, D. 24 cm and Surrounding François GIRARDON (Troyes, 1628 - Paris, 1715) BUST OF A ROMAN GENERAL France, late 17th century White marble; red marble pedestal H. 84 cm, W. 62 cm, D. 23 cm These two busts, forming a counterpart, represent two illustrious Romans, the most famous orator and a general who probably led the African campaigns. The white marble bust, draped in a heavy toga trimmed with fine bangs, presents a familiar face. The face of an important Roman orator, whose bust is in the Uffizi and whom tradition has long identified with Cicero (fig. 1). This head, rediscovered in the first half of the 17th century in Rome during the construction of the church of Saint Ignatius, was first given to Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, who then gave it to Cardinal Leopold de Medici. In 1695, Prince Johann Andreas I of Liechtenstein acquired a bronze copy by the Medici sculptor (fig. 2). In seventeenth-century Europe, Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 B.C.) was a model of an honest man, one who mastered the genre of conversation. His De Officiis was to be used in the writing of civility treatises, while his marble portrait would adorn aristocratic homes. Like the bust in the Duc d'Aumale's old collection (fig. 3) or ours, which is based on the antique head now in the Uffizi in Florence (fig. 1). The other bust, also in marble, represents a leader of the Roman army, a General or an Emperor. His cuirass is stamped with an elephant in a medallion in a laurel wreath, which evokes ancient coins but could also suggest victories in Africa. The tunic escaping from the collar, the pleated and fringed drape clasped to the pectoral, the chain of openwork medallions floating in a scarf are borrowed from François Girardon's bust of Alexander (fig. 4). The sculptor had completed the porphyry head that Mademoiselle Aguillon had given him for the tomb of Cardinal de Richelieu. The accessories of the costume were made of gilded bronze. The bust of Alexander, exhibited at the Academy in 1699 and bought by the King in 1738, belonged to the artist's personal collection. He had set up a gallery at the back of his studio in the Louvre, which he made visit and which he had drawn by his sculptor pupil René Charpentier and then engraved by Nicolas Chevallier. The Gallerie de Girardon printed in Paris in 1709 opened with this figure of Alexander (fig. 5). It was known to the whole of Paris, but only a skilled chiseler, familiar with the work and the manner of the master, could have appropriated with such intelligence those details of the costume which make the genius of our bust. Our two remarkable busts would have had their place, together, in the collection of a great art lover in the Europe of the XVIIth century as the Girardon Gallery or the old royal collections testify.

26

TWO BUSTES forming a counterpart OF ROMAN STATE MEN BUSTE OF CICERON Italy, late 17th century White marble; painted wooden pedestal in imitation of marble H. 81 cm, W. 60 cm, D. 24 cm and Surrounding François GIRARDON (Troyes, 1628 - Paris, 1715) BUST OF A ROMAN GENERAL France, late 17th century White marble; red marble pedestal H. 84 cm, W. 62 cm, D. 23 cm These two busts, forming a counterpart, represent two illustrious Romans, the most famous orator and a general who probably led the African campaigns. The white marble bust, draped in a heavy toga trimmed with fine bangs, presents a familiar face. The face of an important Roman orator, whose bust is in the Uffizi and whom tradition has long identified with Cicero (fig. 1). This head, rediscovered in the first half of the 17th century in Rome during the construction of the church of Saint Ignatius, was first given to Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, who then gave it to Cardinal Leopold de Medici. In 1695, Prince Johann Andreas I of Liechtenstein acquired a bronze copy by the Medici sculptor (fig. 2). In seventeenth-century Europe, Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 B.C.) was a model of an honest man, one who mastered the genre of conversation. His De Officiis was to be used in the writing of civility treatises, while his marble portrait would adorn aristocratic homes. Like the bust in the Duc d'Aumale's old collection (fig. 3) or ours, which is based on the antique head now in the Uffizi in Florence (fig. 1). The other bust, also in marble, represents a leader of the Roman army, a General or an Emperor. His cuirass is stamped with an elephant in a medallion in a laurel wreath, which evokes ancient coins but could also suggest victories in Africa. The tunic escaping from the collar, the pleated and fringed drape clasped to the pectoral, the chain of openwork medallions floating in a scarf are borrowed from François Girardon's bust of Alexander (fig. 4). The sculptor had completed the porphyry head that Mademoiselle Aguillon had given him for the tomb of Cardinal de Richelieu. The accessories of the costume were made of gilded bronze. The bust of Alexander, exhibited at the Academy in 1699 and bought by the King in 1738, belonged to the artist's personal collection. He had set up a gallery at the back of his studio in the Louvre, which he made visit and which he had drawn by his sculptor pupil René Charpentier and then engraved by Nicolas Chevallier. The Gallerie de Girardon printed in Paris in 1709 opened with this figure of Alexander (fig. 5). It was known to the whole of Paris, but only a skilled chiseler, familiar with the work and the manner of the master, could have appropriated with such intelligence those details of the costume which make the genius of our bust. Our two remarkable busts would have had their place, together, in the collection of a great art lover in the Europe of the XVIIth century as the Girardon Gallery or the old royal collections testify.