Description

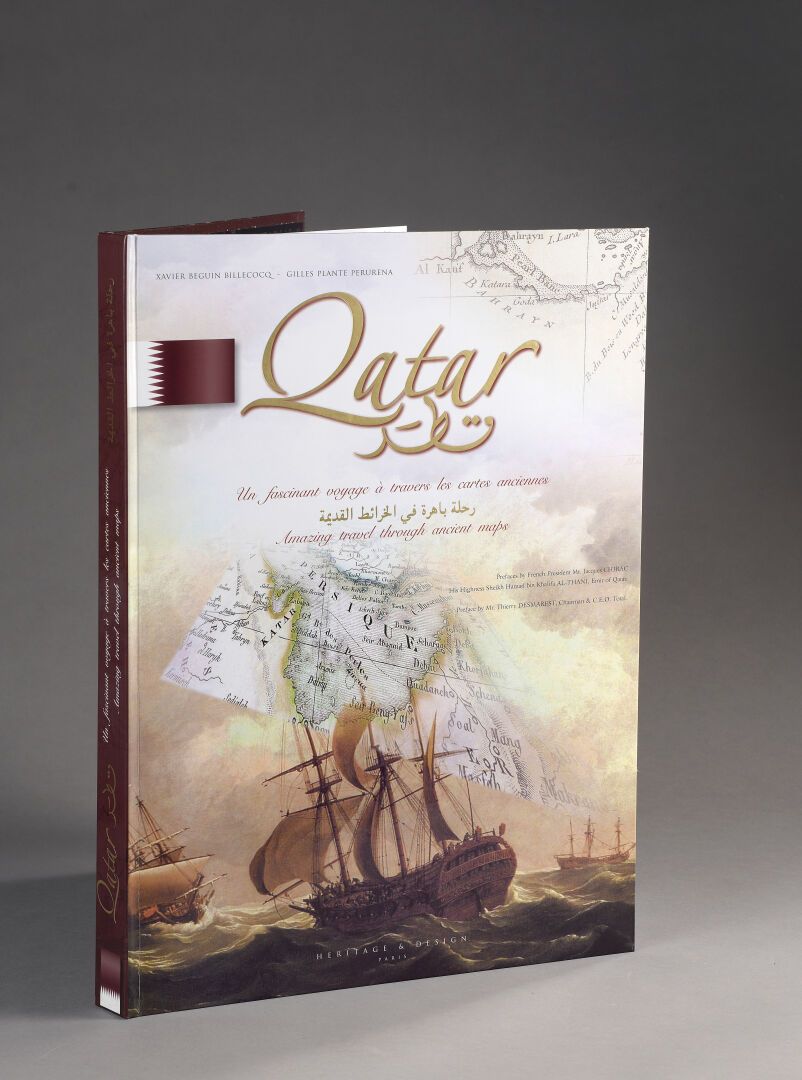

Xavier BEGUIN BILLECOCQ and Gilles PLANTE PERURENA. QATAR a fascinating journey through ancient maps, Paris, Heritage & Design, 2006, in-folio in its box. Forewords by Jacques Chirac, Hamad Bin Khalifa Al-Thani, Thierry Desmarest.

39

Xavier BEGUIN BILLECOCQ and Gilles PLANTE PERURENA. QATAR a fascinating journey through ancient maps, Paris, Heritage & Design, 2006, in-folio in its box. Forewords by Jacques Chirac, Hamad Bin Khalifa Al-Thani, Thierry Desmarest.

You may also like